Drivetrain

Drivetrain

The rotational force of the engine’s crankshaft turns other shafts and gears that eventually cause the drive wheels to rotate. The various components that link the crankshaft to the drive wheels make up the drivetrain. The major parts of the drivetrain include the transmission, one or more driveshafts, differential gears, and axles.

Transmission

The transmission, also known as the gearbox, transfers power from the engine to the driveshaft. As the engine’s crankshaft rotates, combinations of transmission gears pass the energy along to a driveshaft. The driveshaft causes axles to rotate and turn the wheels. By using gears of different sizes, a transmission alters the rotational speed and torque of the engine passed along to the driveshaft. Higher gears permit the car to travel faster, while low gears provide more power for starting a car from a standstill and for climbing hills.

The transmission usually is located just behind the engine, although some automobiles were designed with a transmission mounted on the rear axle. There are three basic transmission types: manual, automatic, and continuously variable.

A manual transmission has a gearbox from which the driver selects specific gears depending on road speed and engine load. Gears are selected with a shift lever located on the floor next to the driver or on the steering column. The driver presses on the clutch to disengage the transmission from the engine to permit a change of gears. The clutch disk attaches to the transmission’s input shaft. It presses against a circular plate attached to the engine’s flywheel. When the driver presses down on the clutch pedal to shift gears, a mechanical lever called a clutch fork and a device called a throwout bearing separate the two disks. Releasing the clutch pedal presses the two disks together, transferring torque from the engine to the transmission.

An automatic transmission selects gears itself according to road conditions and the amount of strain on the engine. Instead of a manual clutch, automatic transmissions use a hydraulic torque converter to transfer engine power to the transmission.

Instead of making distinct changes from one gear to the next, a continuously variable transmission uses belts and pulleys to smoothly slide the gear ratio up or down. Continuously variable transmissions appeared on machinery during the 19th century and on a few small-engine automobiles as early as 1900. The transmission keeps the engine running at its most efficient speed by more precisely matching the gear ratio to the situation. Commercial applications have been limited to small engines.

Front- and Rear-Wheel Drive

Depending on the vehicle’s design, engine power is transmitted by the transmission to the front wheels, the rear wheels, or to all four wheels. The wheels receiving power are called drive wheels: they propel the vehicle forward or backward. Most automobiles either are front-wheel or rear-wheel drive. In some vehicles, four-wheel drive is an option the driver selects for certain road conditions; others feature full-time, all-wheel drive.

The differential is a gear assembly in an axle that enables each powered wheel to turn at different speeds when the vehicle makes a turn. The driveshaft connects the transmission’s output shaft to a differential gear in the axle. Universal joints at both ends of the driveshaft allow it to rotate as the axles move up and down over the road surface.

In rear-wheel drive, the driveshaft runs under the car to a differential gear at the rear axle. In front-wheel drive, the differential is on the front axle and the connections to the transmission are much shorter. Four-wheel-drive vehicles have drive shafts and differentials for both axles.

The Differential

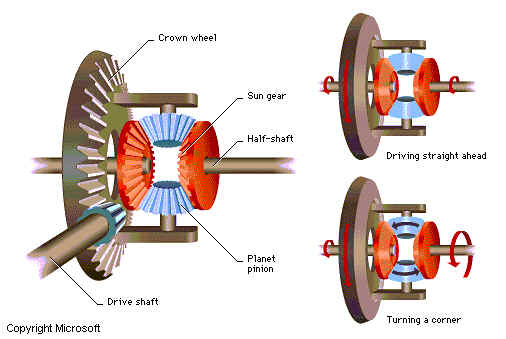

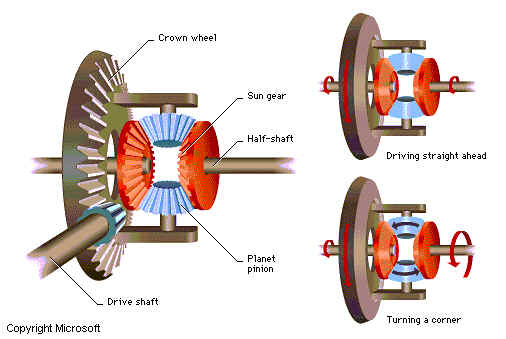

The gears of a differential allow a car's powered wheels to rotate at different speeds as the car turns around corners. The car's drive shaft rotates the crown wheel, which in turn rotates the half shafts leading to the wheels. When the car is traveling straight ahead, the planet pinions do not spin, so the crown wheel rotates both wheels at the same rate. When the car turns a corner, however, the planet pinions spin in opposite directions, allowing one wheel to slip behind and forcing the other wheel to turn faster.